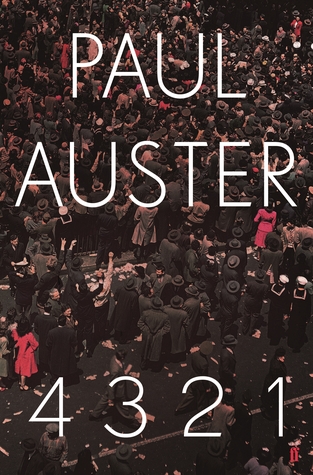

Yes, anything was possible, and just because things happened in one way didn't mean that they couldn't happen in another. Everything could be different. The world could be the same world, and yet if he hadn't fallen out of the tree, it would be a different world for him, and if he had fallen out of the tree and not just broken his leg but had wound up killing himself, not only would the world be different for him, there would be no world for him to live in anymore, and how sad his mother and father would be when they carried him to the graveyard and buried his body in the ground, so sad that they would go on weeping for forty days and forty nights, for forty months, for four hundred and forty years.4 3 2 1 is a mashup of Bildungsroman meets The Butterfly Effect by way of post-modernism and The Great American Novel. It is the story of one Archie Ferguson – suburban New Jersey Jewish boy, only beloved child of Rose and Stanley, a wannabe writer from earliest childhood – whose four possible life stories are detailed from the Eisenhower to the Nixon administrations. Reading the newspaper reviews for this book, I learned two things: much of the biographical information for Archie mirrors that of author Paul Auster; and it's perfectly acceptable to consider this book to be too long by half, with ponderous stretches of cerebellum-numbing logorrhea. It will probably win awards. Spoilers from here.

As the book began, I was completely charmed by Archie's origin story – where his parents came from and how they met – and I appreciated the dense, info-rich paragraphs that, at the time, seemed an efficiency; a shortcut to understanding. On Stanley's mother:

The still energetic Fanny Ferguson, in her mid- to late sixties by then, who stood no taller than five-two or five-two-and-a-half, a white-haired sourpuss of scowling mien and fidgety watchfulness, muttering to herself as she sat alone on the couch at family gatherings, alone because no one dared go near her, especially her five grandchildren, ages six to eleven, who seemed positively scared to death of her, for Fanny thought nothing of whacking them on the head whenever they stepped out of line (if infractions such as laughing, shrieking, jumping up and down, bumping into furniture, and burping loudly could be considered out of line), and when she couldn't get close enough to deliver a whack, she would yell at them in a voice loud enough to rattle the lampshades.But eventually, these dense, info-rich paragraphs got on my nerves: surely, in an 866 page book, some of this is peripheral? And this applied not just to the technique, but the entire scope became just too much, eventually covering:

The war in Vietnam, the civil rights movement, the growth of the counterculture, developments in art, music, literature, and film, the space program, the contrasting tonalities between the Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon administrations, the nightmare assassinations of prominent public figures, racial conflict and the burning ghettos of American cities, sports, fashion, television, the rise and fall of the New Left, the fall and rise of right-wing Republicanism and hard-hat anger, the evolution of the Black Power movement and the revolution of the Pill, everything from politics to rock and roll to changes in the American vernacular, the portrait of a decade so dense with tumult it had given the country both Malcolm X and George Wallace, The Sound of Music and Jimi Hendrix, the Berrigan brothers and Ronald Reagan.So, to the interesting format: 4 3 2 1 begins with a chapter 1.0; the one common origin story for every Archie Ferguson. The next chapter is 1.1, followed by 1.2, 1.3, and 1.4; four slightly different childhoods, primarily changed by the actions of Archie's ne're-do-well uncles. It took me a while to understand that this branching of Archie into four same/not-same characters was happening, but as the book progresses, what started as small differences become major changes in character and circumstance: grandparents die in different orders; most Archies are sports fanatics and one is not; one Archie plasters his room with JFK posters, and while most are politically engaged, one finds everything about politics to be boring; they are all obsessed with sex as young teenagers, and while they have varying degree of success with the ladies, one of them becomes a lifelong bisexual because of a chance encounter in a movie theatre (and is Auster saying that some percentage of homosexuality just comes down to opportunity?) I said there would be spoilers, so I will point out that the book goes on until three of the Archies die (leaving us with the [presumably] original Archie who conceives of writing a book about his alternate possible lives), and when you get to a chapter that should feature an Archie who has passed (let's say 3.2 or 7.3), there's just a blank page (which I found interesting and shocking...the first time).

So ends the book – with Ferguson going off to write the book.So, what's the point? As in the opening quote, Archie is quite young when it occurs to him that small changes in his decisions/actions could amount to huge changes in his life, and in another storyline, he takes this to be proof of God: if it's possible to imagine all of these parallel lives playing out simultaneously, only an omniscient being could observe them at the same time. There are many references to the path not taken, one storyline sees one of the Archies writing a short story about a character who explores every fork on a road, and whenever something surprising happens to one of the Archies, there's mention made of an entry having been made in The Book of Terrestrial Life – as though everything is preordained – and the observing gods either smile or shrug. At the end of the book, after a decade of deaths and protests and war and government lies, a decade in which a young man Archie's age would have felt very little control (and especially with the draft), the last/original Archie decides to write this book about parallel lives; turning himself into the omniscient being; the one with control.

In the end, this book just felt too long. It's so incredibly full of detail – from a blow-by-blow of the student takeover of Columbia University in 1968 to a half-page list of every British actor who made it big in Hollywood – and in many cases, the level of detail about small things made them seem the most autobiographical (and then I had to wonder which Archie's experience was the most like Auster's, but the moments of truthiness were scattered throughout and I couldn't point to any one of them as more realistic than another). And the subject matter – the politics of the Sixties – feels a little dated; this just might have been the Great American Novel if it had come out in the Seventies, but without, say, making any connections from the Black Power movement to BLM, or making the quagmire of Vietnam analogous to the present day Middle East, it seems to be just what it appears to be: a retelling of the events of fifty years ago, which are obviously more important to the author than they are to me.

And here's the other thing I learned from reading the newspaper reviews of 4 3 2 1: this long and meandering (dull) format is a departure for Auster. Everyone is full of praise for his earlier works, so I won't dismiss him entirely. I can totally appreciate what he was going for here, but I was sighing too much before the end to go any higher than three stars.

The Man Booker 2017 Longlist:

4 3 2 1 by Paul Auster

Days Without End by Sebastian Barry

History of Wolves by Emily Fridlund

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid

Solar Bones by Mike McCormack

Reservoir 13 by Jon McGregor

Elmet by Fiona Mozley

The Ministry Of Utmost Happiness by Arundhati Roy

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders

Home Fire by Kamila Shamsie

Autumn by Ali Smith

Swing Time by Zadie Smith

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

Days Without End by Sebastian Barry

History of Wolves by Emily Fridlund

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid

Solar Bones by Mike McCormack

Reservoir 13 by Jon McGregor

Elmet by Fiona Mozley

The Ministry Of Utmost Happiness by Arundhati Roy

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders

Home Fire by Kamila Shamsie

Autumn by Ali Smith

Swing Time by Zadie Smith

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

Eventually won by Lincoln in the Bardo, I would have given the Booker this year to Days Without End. My ranking, based solely on my own reading enjoyment, of the shortlist is:

Autumn

Exit West

Lincoln in the Bardo

Elmet

4321

History of Wolves