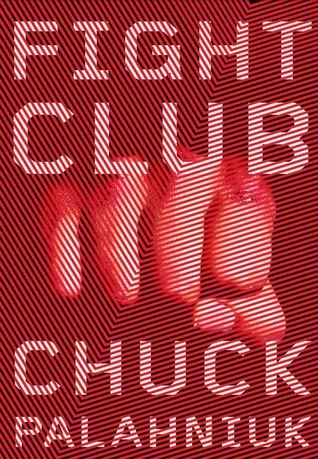

Man, I see in Fight Club the strongest and smartest men who've ever lived. I see all this potential, and I see it squandered. God damn it, an entire generation pumping gas, waiting tables – slaves with white collars. Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy shit we don't need. We're the middle children of history, man. No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our great war is a spiritual war. Our great depression is our lives. We've all been raised on television to believe that one day we'd all be millionaires, and movie gods, and rock stars, but we won't. And we're slowly learning that fact. And we're very, very pissed off.Here's my history with Chuck Palahniuk: I saw the movie version of Fight Club when it was first released on video and I was impressed by its rawness and its philosophy and its unapologetically macho vibe. Because I now knew its twists, however, I didn't think I'd ever need to read the book. I eventually picked up some other Palahniuk – Survivor, Invisible Monsters, Pygmy, Damned, Choke – and other than the last one, I pretty much hated all of these but keep reading more, thinking, “He must have written another Fight Club and I want to find it.” Eventually, I gave in and just read Fight Club, and here's the thing: even knowing the twists and having a vague memory of the main details, this was a highly entertaining and interesting read, and what's more, Palahniuk's writing (which couldn't quite be captured by the film) was totally impressive to me. Conclusion: if you're trying to find a book to read like Fight Club, you ought to just read Fight Club. This will be a little spoilery.

The first rule of Fight Club is: you do not talk about Fight Club. The second rule of Fight Club is: you DO NOT talk about Fight Club.By now that's a cliche, but like most cliches, that started off as iconic; don't pretend you've never thought the rules were cool. Here's what's even cooler: In the afterword of my edition, Palahniuk writes that one of his inspirations for writing this book was the popularity of Oprah's Book Club and of novels like The Joy Luck Club and How to make an American Quilt – all focussed on how groups of women can get together and talk and relate with one another – and he wanted to create a way for groups of men to make these same connections; and not only would his club not involve talking, but members were strictly forbidden to talk about it with others. This book is anti-talk, all action, with 30-something man-childs putting their bodies on the line because history isn't giving them a reason to prove themselves, and for the most part, they grew up without fathers to teach them how a man should be.

If you’re male and you’re Christian and living in America, your father is your model for God. And if you never know your father, if your father bails out or dies or is never at home, what do you believe about God?Our unnamed narrator is just this adrift; his life so devoid of meaning that he attends group therapy for conditions he doesn't have in order to vampire emotions from those who are really suffering. His life is so empty that when he meets the charismatic Tyler Durden – a man who says, “Would you do me a favour and hit me as hard as you can?” – our narrator discovers cleansing through pain; his insomnia finally cured. Through Tyler he embraces a transgressive philosophy that states you can fight back against society from whatever low rung on the ladder you occupy – splicing pornography into Disney movies, peeing in the soup tureen at a fancy catering gig – and when necessary, the fight can be elevated to guns and homemade bombs. That the narrator is so quick to abandon his former white-collar life and join Tyler in his soap-making and army-building gives a very pointed critique of our meaningless society; which then becomes this big ironic turnaround with the final reveal (which is somehow both more thoroughly set up and subtle in the book as compared with the movie). You don't need to be crazy to work here, but it helps.

Marla's philosophy of life, she told me, is that she can die at any moment. The tragedy of her life is that she doesn't.Marla is a much more complicated character in the book – probably because in the movie she needs to act like a doormat and not ask too many questions that might give everything away – and that upped my enjoyment. I didn't include this following bit in my goodreads review, because I acknowledge it's rather offensive (and also because I don't remember if it's in the movie; yet I'm thinking it's so Marla that it must be), but when she tells Tyler "I want to have your abortion", I was struck by how perfectly that captures what a messed up person Marla is. No matter where a person falls on the Prolife-Prochoice divide, who would offer that out as a tragically romantic proposition? It's so offensive in concept to me, but I am not offended in actuality because I can kind of see what Marla means by that; and that's a deft authorial accomplishment. The writing overall pleased me: the way that Palahniuk used repetition and circling was poetic and satisfying without feeling gimmicky. I appreciated the irony of the narrator's favourite group therapy session at the beginning of the book (Remaining Men Together; for men who've lost testicles to cancer) being mirrored by the threat of castration at the end (and the overall theme of the emasculation of the modern man). Even the twist didn't seem gimmicky because it felt organic – a slow revelation of a sickness instead of an unjustified trick.

In the end, I did enjoy Fight Club very much but it seems to reinforce what I pretty much already knew: Palahniuk probably only had one really good book inside him, and while I am pleased to have finally read it, it will take a powerfully persuasive recommendation to make me pick him up again.