The most wonderful enchanted things happen here -- the most enchanted things you can imagine. I want to tell you while I still have time, before they close the black curtain and I take my final bow.A few years ago, Titus Andronicus was one of the plays showing at the Stratford Shakespeare Festival, and after seeing it in a preview performance, my 15-year-old daughter was interviewed as part of the filming for a promo piece. She described it as, "Incredibly moving, brutal and beautiful". Not long after that, the whole family went and we agreed with her review -- the staging of this play was incredible and the aftermath of the rape of Lavinia (who had had her tongue and hands removed so as not to accuse her attackers) was unlike anything we had ever seen on stage. Months later, I won two premium tickets to the same play, and thinking it would be a special treat for them, I gave the tickets to my inlaws. Having seen their granddaughter's interview online, they were excited to go see the play, but unfortunately, my mother-in-law barely made it to intermission before she had to leave the theater: the rape and Lavinia's bloody aftermath were so disturbing that she walked down to the river to watch the swans and contemplate what her granddaughter had found so beautiful, leaving my father-in-law to watch the second act alone.

|

| From a different production with a similar treatment |

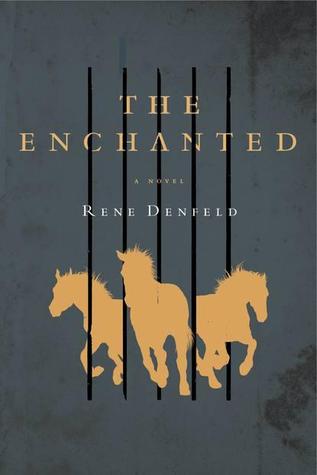

As Keats said, "Beauty is truth, truth beauty", and just as the staging of Titus Andronicus was beautiful because of its truthful treatment of ugly themes, The Enchanted is a beautiful, beautiful, book; not despite its terrible events but because of its terrible truths. The book begins with an unnamed (for now) narrator: a Gollum-like mute who cowers and cringes in his death row cell, unwilling to talk to or be seen by anyone, but able to discern the secret enchantments of the prison.

I see the soft-tufted nightbirds as they drop from the heavens. I see the golden horses as they run deep under the earth, heat flowing like molten metal from their backs. I see where the small men hide with their tiny hammers, and how the flibber-gibbets dance while the oven slowly ticks.The Enchanted is framed through this narrator's experiences, and so the only other characters are inmates and guards that he used to know in the general population, his fellow death row inmates, and those who have access to them: the warden, the fallen priest, and the lady (and in keeping with what he knows, these three essential characters are never called by their actual names) . "The lady" is a death penalty investigator -- a person who is hired to uncover information that might stay an execution -- and a handful of other characters are introduced as she investigates the background of another convict named York (giving the narrator a type of selective omniscience that is in keeping with his ability to see beyond the here and now). The information the lady discovers is disturbing and touches her viscerally, which in turn touches the reader viscerally.

The author, Rene Denfeld, is a death penalty investigator and journalist who has written nonfiction books about women and violence and street kids. I've read a few books lately by nonfiction authors who have made the leap to their first novel, and this is the first time that it feels successful -- Denfeld put everything she knows into this work (it has smarts) and writes in the voice of a poet (it has heart). Early on she says of the lady:The look in her eyes is of a person who drank from the end of a gun barrel and found it delicious. I'm not even 100% sure what that means in a literal sense, but it touched me on a deeper level and I devoured this book, breathless and enchanted. As horrific as some of the scenes of childhood abuse and neglect were, the presumably most brutal scenes (the actual crimes for which the convicts were condemned) are only hinted at, and although we know they must all be monsters -- including the narrator -- I wept when the warden showed Arden compassion by giving him a new copy of The White Dawn.

There is much art in this book and it spoke to my specific art receptors; my truth -- yet if someone were to close The Enchanted halfway through and go to look at the swans, I would understand; it might not be for everyone. The white-haired boy tossing out helpme notes and the wife reaching for her bedside wig and the girl with the bright pink beanbag chair are minor characters that are going to live with me for a long time. For me, the narrator egging on the golden horses (Go, horses! Go!) was entirely thrilling (and to anyone who dismisses these scenes as weak magical realism: I would encourage that person to remember that the narrator was raised in a mental hospital and consider that what he thinks he "sees" might just be in his mind…) and, as in my reaction to 1Q84, the little men in the walls triggered some kind of powerful Jungian subconscious reaction in me.

The little men with hammers are in the walls of my cell. I'm not sure how they get here so quickly. One minute the walls are silent and the next they are there, sometimes in force. They have a very distinctive smell, like wet sawdust and urine. They scamper through tunnels under the yard and under the buildings like gophers, until all of a sudden they pop up here, dozens of them…The little men don't care about me. I am just one of the cordwood bodies they scamper over in the night, eating the dead skins off the soles of our feet.As a death penalty investigator, Denfeld uses all of the tools of literary fiction in The Enchanted to reveal deeper truths about those she would defend: the condemned are human first and we treat them monstrously at the risk of our own humanity. Tis a beautiful, horrible truth.

This was a book reviewed in the newspaper I read and their discussion is here.